In the following weeks, I am going to introduce the reader to various lectures, essays, and books, that have shaped my outlook on science and its place in the culture. This week I am examining a commencement address that Richard Feynman gave to the graduating class of 1974 at CalTech.

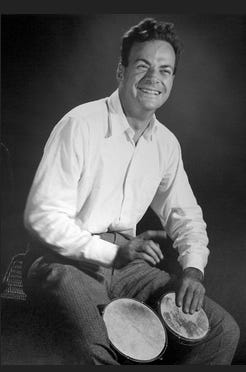

Richard Feynman is widely known as an amiable, inquisitive and very intelligent scientist. His humor and manner of explaining scientific concepts has made him a popular figure. I have admired his work in physics ever since college where I used his physics lectures as a textbook. The antics he relates in books like Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman only added to his appeal for me. His playful manner and sense of adventure resonated with me. I find his views on the teaching and the practice of science, however, to be the most insightful material he produced.

Feynman’s address to the Class of 1974, known as Cargo Cult Science, is an example of his appreciation for the purity of science. In his talk he advised graduates to have an unwavering integrity when reporting on their scientific discoveries. Feynman warns of several temptations that are inherent in academic science today. He points out that the pressure to publish might entice a person to skip steps. The desire to have an air-tight proof for their hypothesis might cause one to leave out information that does not fit the conclusions. The need to gain funding for research could cause a scientist to exaggerate the benefits of a certain course of study. He warns that if you give into any of these temptations, you are not being honest with yourself or others. This is the path that leads to Cargo Cult Science.

What exactly does Feynman mean by this term? He explains in this passage (I cannot vouch for the validity of his story).

“During [World War II, Pacific Islanders] saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So, they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So, I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.”

He gives this example to contrast real scientific work with pseudo-scientific subjects like UFOs, astrology and numerology. People who use these practices try to borrow the form of science, with elaborate rationalizations for their beliefs. But in the end, their predictions and conclusions don’t fit with reality. Or, as he states, “the planes don’t land”.

What does real science do differently? He describes it here.

“Then a method was discovered for separating the ideas—which was to try one [idea or conclusion] to see if it worked, and if it didn’t work, to eliminate it. This method became organized, of course, into science. And it developed very well, so that we are now in the scientific age. It is such a scientific age, in fact, that we have difficulty in understanding how witch doctors could ever have existed, when nothing that they proposed ever really worked—or very little of it did.”

This is the method those pseudo-sciences borrow, but their results don’t pan out. Feynman identifies the reason.

“But there is one feature I notice that is generally missing in Cargo Cult Science. . . . It’s a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty—a kind of leaning over backwards.“

Feynman offers several examples of what this integrity looks like.

“For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid—not only what you think is right about it: other causes that could possibly explain your results; and things you thought of that you’ve eliminated by some other experiment, and how they worked—to make sure the other fellow can tell they have been eliminated.”

“Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can—if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong—to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it.”

This last point, to me, is the most important and one that I feel is absent from many important topics these days.

He goes on to make a special emphasis on communicating with the public.

“[You] should not fool the layman when you’re talking as a scientist. . . . I’m talking about a specific, extra type of integrity that is not lying, but bending over backwards to show how you may be wrong, that you ought to do when acting as a scientist. And this is our responsibility as scientists, certainly to other scientists, and I think to laymen.”

And finally, he admonishes the graduates:

“In summary, the idea is to try to give all of the information to help others to judge the value of your contribution; not just the information that leads to judgment in one particular direction or another.”

This is excellent advice for any scientist. But it should also be practiced by those who communicate important scientific discoveries applicable to important topics. Imagine how different the public discourse would be regarding the big scientific issues of the day if the bureaucrats, politicians, pundits and celebrity scientists practiced “utter honesty”. But they do not.

This has been a source of great frustration to me. The lack of honesty has started to tarnish science’s reputation. You can test this claim by Googling the phrase “distrust of science”. You will get hundreds of results discussing the topic and even find articles that attempt to explain why this is happening. I think you don’t have to look any further than Feynman’s explanation – there a lack or integrity in those representing the science to the public.

This series of essays will be an exploration of how I believe we got to this state. The next essay in the series discusses how Carl Sagan shaped my views on science.